Volume III ● Issue 2/2012 ● Pages 211–220

Re-visiting the Visibility of the Grape, Grape Products, By-products and some Insights of its Organization from the Prehistoric Aegean, as Guided by New Evidence from Monastiraki, Crete

Anaya Sarpakia*

aIndependent scholar, 137 Tsikalarion Rd., Tsikalaria, Souda,73200 Crete, Greece

Article info

Article history:

Received: 25 May 2012

Accepted: 10 September 2012

Key words:

Prehistoric Crete

wine

archaeobotany

grape products

grape organization

Abstract

The archaeology of the grape has been studied quite thoroughly from the angle of the technology of wine-pressing, wine making installations and the archaeobotany of the grape plant, its origin and dispersion. The grape though is elusive archaeobotanically, even in to wine-producing areas, due to the fact that traded wine is often filtered and can only be detected by chemical analyses. Monastiraki in Crete, though, a Middle Bronze Age site, has provided us with information on the organization of grape-pressing, methods of wine-making and, perhaps, offers insights into the organization of wine and vine products, data which other Prehistoric sites in Crete had not revealed so far.

1. Introduction

There is no doubt that the grape played a very important role in most of the aspects of life and death of the Prehistoric Aegean. Its invisibility or rather its poor visibility, in the archaeological record, has already been discussed in the past (Sarpaki 1995), but this has not overridden the glow of its importance, in most periods of prehistory and history of the Greek peninsula and islands. However, in this paper only the primary data of the grape will be presented, namely the archaeobotany, and more specifically the macroscopic fruit remains, as research has moved on since the earlier discussion of the topic. Subsequently, the indirect evidence will be mentioned, which is the so-called wine installations but I shall not dwell on these as they have already been presented extensively and in detail by Kopaka and Platon (1993).1 The aim in doing so, is not to prove that the grape (the wild and the domesticated grape) was present in the area, which is known as Greece today, since very early times. This is a known fact but some further evidence will be presented. Therefore, it is time for us to go beyond the question which has occupied archaeologists for a century; that is: “was grape indigenous to the Aegean”? Our questions should be redefined to: “where were grapes systematically tended and cultivated at first and then domesticated? Were they cultivated for local consumption? When and where were they considered, so to speak, a cash crop and wine systematically produced?” It is, therefore, levels and types of cultivation and levels and types of specialization that need to occupy our research now.

2. The archaeobotany

We shall, therefore, not delve into discussions relating to the area of origin of the vine. It is an accepted fact, based on fossil evidence, that, during the Pleistocene, Vitis vinifera ssp. sylvestris survived in the forests encircling the Mediterranean (Olmo 1995, 36; Buxó 1997, 277) and along the southern shores of the Caspian Sea. The present distribution of the wild vine, in the areas which will be discussed, is enlightening.2 (Figure 1). We, therefore, need to note that the whole of Greece, the islands and Crete have populations of wild/spontaneous vine, V.vinifera ssp. sylvestris. In the Neolithic as well, generally speaking, the wild grape must have occupied the same areas, (Logothetis 1962; Olmo 1995, 36) which, of course, further complicates our problem of: “where was it first used”, and whether it was systematically used (cultivated) in its wild/spontaneous form, before becoming widespread in its domesticated form.

Regarding the domestication of the vine, we are still at a loss. There have been several studies concerning the identification of grape pips and their separation, on morphological grounds, into wild and cultivated, with one of the latest being a study published by Mangafa and Kotsakis (1996). In their study, several metric characteristics of the grape pip have been used but, unfortunately, the application of these criteria has not worked successfully, when applied to archaeobotanical material from two sites in the Mediterranean, namely Petra (140 BC–AD 40)( Jacquat, Martinoli 1999) and Coast Mochlos (L.M.IB) (Sarpaki, Bending 2004). Using the criteria identified in the formula and published by Mangafa and Kotsakis, has led Martinoli and Jacquat (1999), as well as Sarpaki and Bending (2004), into erroneously identifying wild grapes in archaeobotanical samples which, most probably, only had domesticated grape.3 It is clear that enrichment of the formula and the data needs to be pursued by measuring other populations of wild grapes4 and additional measurements of cultivated varieties.5 Furthermore, additional work is, most probably, needed, not so much on the metric characteristics but rather, on their ratio indexes. The result is that, at present, except for very typical wild grape pips, there are no metric criteria to be used, confidently, in order to discriminate between them and we are left with the older general morphological criteria used by Stummer (1911) and Schiemann (1953).

The Vitis pollen is also not separable into wild and domesticated. The only rough criterion is the quantity of pollen grains that each plant produces but, definitely, not their morphology. We know that wild grape is dioecious, which means that some vines have only female flowers, and others have only male, which produce pollen. In the domesticated vine, both male and female flowers, though, retain the organs of the more primitive hermaphrodites, although in a more rudimentary stage of development. The only criterion, which could, possibly, be used, is the larger quantity of pollen that the wild vine produces. Bottema and Sarpaki (2003, 735) had observed that wild grape pollen, in a sample from an area where wild vines grew, was in the order of 29.7%, whereas pollen trapped from fields, where domesticated vine grew, was in the order of 2.3%. Therefore, the only criterion, which could be used, at present, is the percentage of pollen counts, i.e., paradoxically, high pollen count for wild vine and low for domesticated or monoecious and self-fertilised.

Charcoal studies, as well, have similarly not helped in discriminating between wild and cultivated vine wood but Terral (2002) has tried to (a) quantify anatomical criteria in order to differentiate between the two; (b) identify wild individuals growing in natural conditions from wild but cultivated individuals; (c) identify mature wood from stems versus immature wood from vine shoots. The conclusions of his experiments are not yet definitive but they need to be tested further, and applied to archaeological material.

In brief, we can therefore conclude that the sub-fields of archaeobotany have still some way to go before the questions of wild versus domesticated and naturally wild versus wild but cultivated can be resolved.

3. Applied archaeobotany

Regarding the first question: “where were grapevines systematically cultivated in Greece? And when?” We cannot provide a strict scientific answer but rather an intuitive, knowledgeable comment based on up-to-date observation. If we observe the grapevine finds in Greece (Table 1, also Valamoti 2009, 208–209) we come to realize its presence in the north and in Thessaly from the E.N. and evidence of the making of juice/wine from morphologically wild grapes from Dikili Tash dated as early as the 5th millennium BC in the north of Greece. However, these morphologically wild grapes might also have been the products of cultivation (Valamoti et al. 2007). Nevertheless, it is important to stress that wine could be produced from the wild grapevine (Valamoti et al. 1998, 145; Singleton 1995, 72–73; Nứñez, Walker 1989) and this production would have “influenced” the evolution of morphologically domesticated characteristics. Even though it would have a considerably lower sugar content, wine would result as easily, and it is known that wild grapes reach 18% sugar or more and when dried in dry and warm countries can reach even higher levels (Singleton 1995).

In Crete (Table 2) grape pips make their appearance in Early Neolithic II at Knossos, at approximately the same time as in Northern Greece, i.e. 5th millennium (Valamoti 2004). The findings of grape pips at the sites most probably argue in favour of their edible use. Whether the Knossos pips were wild, cultivated, or domesticated, we are still not sure, although we submitted them to the formula mentioned above (Mangafa, Kotsakis 1996) and they were clustered within both wild and domesticated categories. We can, therefore, claim that the data indicates that the grape (wild and/ or cultivated) was present in Greece from the north to the south since, at since, the Early Neolithic – if not earlier. From pollen studies in Crete (Bottema, Sarpaki 2003, 744), there is evidence that Vitis vinifera ssp. sylvestris was present for most, if not all, of the Holocene, whereas in northern Greece in the Younger Holocene (Bottema 1994, 60), pollen of grape either appeared or increased. Therefore, we can conclude, with some degree of confidence, that Vitis vinifera ssp. sylvestris had been well established, in the geographical department of Greece, at least since of the Holocene, if not before.

At some date, which, at present, cannot be securely pinpointed, the grapevine, through isolation and selection shifted from a cross-pollinated and dioecious species to a self-pollinated flower. The location and the date of this event(s) are obscure but, I believe, it should be found in the Early Neolithic period, at least, as wine-making, put aways to be connected to sedentism. Whether the know-how of wine-making from the wild grape was transferred from the Mesolithic economies to the Neolithic, awaits still to be proven. Nevertheless, the whole process of domestication, together with the agricultural tending of the plants and their propagation, i.e. grafting, needs a sedentary-type of existence, as the results of investment takes some time to come to fruition. It takes as much as some ten years and more for vines to produce a significant crop.6 Moreover, as far as we know from domesticated grape, the must can be transported and in antiquity it was done in leather sacks – askoi7 – but then it needs to rest for some time, immobile, for the fermentation to take place. Therefore, populations on the move are not prone to have the right pre-requisites leading to wine-making. Although, wine was exchanged/traded in Prehistory, this took place as must (freshly pressed grapes) and/or after the process of wine-making – fermentation – was completed, and, only then, it could be moved.

4. Structures/Artifacts – indirect evidence – connected to wine pressing

Kopaka and Platon (1993) published a thorough study of the presses-installations excavated from Minoan sites on Crete. They counted some 41 presses of several types. It has been calculated further by Kopaka (1997) that more than another 40 such pottery presses have been uncovered in Minoan Crete, and they are found in central and east Crete. I have reasons to believe (see site of Monastiraki) that, in areas where wood was plentiful, press installations might have been made from available wood and, perhaps, preferably, from timber that includes/exhudes tannins, such as oak.8

Recently, a wine-pressing installation has been uncovered at Akrotiri, Thera in Trench 58B, in the course of the excavations for the new shelter (Figure 2). The archaeobotanical material connected to this find, though, is in the course of being studied and will not be presented here. It is possible that people were treading grapes in the upper lecane (vat) and the grape juice was collected in the lower pithos (open-mouthed jar) with a spout. This is a fairly typical pottery wine-press installation of Minoan Crete and other areas of Greece. The interest lies in the fact that at Akrotiri, Thera, an urban site of which circa 1 hectare has been excavated, only one such wine-pressing installation has been uncovered.9 Therefore, the probability is that wine-pressing was not conducted within the settlement but rather in outlying areas or, perhaps, near the vineyards.

In order to corroborate this point, archaeobotanical material from another important palatial centre of the “Protopalatial” period, which spans from MM I to MM IIB (2000–1700 BC), is presented, the site of Monastiraki, in the Amari valley of Crete.

5. Case study: Monastiraki

Monastiraki seems to have been closely connected to the palatial site of Phaestos for the following reasons:

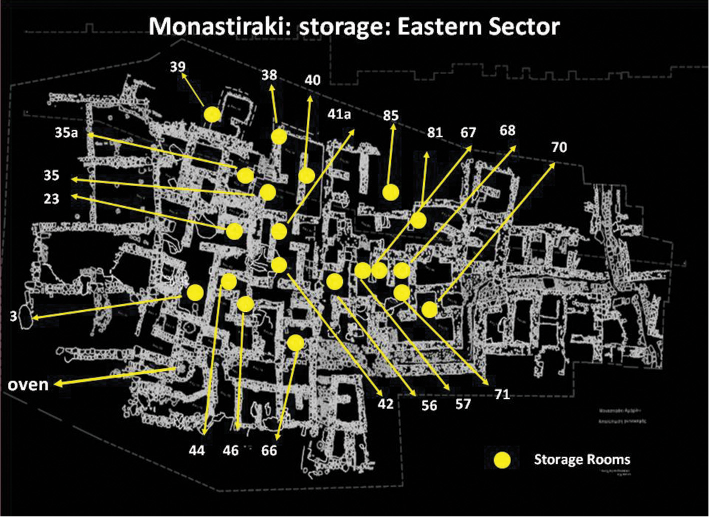

Over 100 rooms have been excavated at Monastiraki from the Eastern Sector alone, of which 17 rooms (Figure 3) have been characterized as storage rooms per se. For this exercise, we defined as a storeroom, rooms which had three (3) or more pithoi and in cases where rooms were small, rooms with two (2) pithoi were also included. On the whole, some 88 (minimum number) pithoi have been found in the Eastern Sector. If we add pithoi of the two other sectors, they amount to 123 pithoi. This, of course, refers to a minimum number (ΜΝ), as the pithoi in rooms with under 2 jars have not been included in this count. Also exluded were instances of storage in, possibly, other types of containers made from organic materials, such as wood, wicker, leather sacks, cloth sacks made from linen and other plant/wool material.

What is of utmost interest though is that actual archaeobotanical finds of grape are numerous in the 3 sectors of the site, although only here, the Eastern Sector is shown (Figure 4). Vine (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivation was, obviously, of paramount importance at Monastiraki and there is no doubt, due to its omnipresence and to the archaeobotanical remains which include grape skins, pips, pedicels and stems, that this was not a product of import. Vine pips, together with the find of stems, pedicels and grape skins in the pots, indicate the presence of must in many samples.

Archaeobotanical evidence of wine-making, as we all know, is rather rarely detected, as the dregs, at some stage, would have been sifted out, after the filling of the pithoi with the must. However, at Monastiraki, in many cases, we seem to be finding the dregs. The interpretation is somewhat fraught with dangers, in that the destruction layer could, simply, be interpreted as representing the time of wine-making, which is September for the south of Greece.10 Nevertheless, it is important to say that, at least, we know that even the first stages of fermentation were spent in the pithoi11 and not in other containers. If that is the case, it could have been possible for the dregs to be sifted out/sieved, all at once. Another interpretation could also be the demonstration that dregs were not sieved, when the wine was stored but only just before its consumption, in a piece-meal fashion. This, perhaps, was a way of making the tannins dilute better/ longer in the mixture, for reasons which need to be investigated further and, also, a way of making sure that wine would be coloured a rather deep red. These would have been the wines which preserved better, in other words had a longer shelf life and, perhaps, tolerated more travel conditions. It is known, for example, that white and rosé wines, have a shorter shelf life and, furthermore, do not travel well.

It is, also, important to note that sites which have a high production of wine, must have also produced related technologies, i.e. the preparation of dried grapes (Mangafa et al. 2001), of molasses from grapes (petimezi in Greek) connected to the production of sweets; the production of vinegar, which was further connected to a whole series of food technologies (preserves), fresh (vegetables, and dairy products), cooked (meats, fish, sauces and vegetables), the production of wine lees which would have been used as a mordant during dyeing. Wood and vine branches could have been used for a multitude of items such as artifacts, architectural parts, baskets, and cordage(?). Related crafts/industries would have been perfumery, textiles (dyeing, mordanting and degreasing of wool), even, perhaps, pottery where vinegar (Nứñez, Walker 1989, 228) prevents sloughing and “enhances the joining of clay elements before vessels are dried and fired”. Possibly sherds could be tested for tartaric acid and anthocyanins which might point to the use of this product in pottery technology.

6. The organisation of grape-pressing

Having discussed Monastiraki and having collected slim information on all other sites, we come to the conclusion that very few areas have been identified for treading grapes. The number of treading areas in Greece and Crete, in particular, are very few, for a culture which attributed so much importance12 to wine. In Crete, Kopaka and Platon (1993) have listed a mere 29 treading areas13 (Table 3). At Monastiraki (Pre-palatial period), for example, with a seemingly large production of wine, none were found. The large Late Cycladic site of Akrotiri in the Cyclades has only produced one (as shown) so far. Our observation are, therefore the following:

1) They are very thin on the ground, approximately 30.

2) Palace sites have none. They are generally found in the settlements connected to the Palace.

3) Their size is rather small compared to the amount of wine which would have been needed. One person seems to have been able to tread, at a time (see Figure 2 – treading vat from Akrotiri, Thera and a depiction on a sealing, CMS II/I, No. 420 – Middle Minoan from Chrysolakkos Malia, of a man treading in a vat – Figure 5).

So what interpretations can be triggered by the data at hand?

Except for the possibility that they could have had treading installations (vats) made of wood in certain areas, which do not leave tangible archaeological evidence, alternatively, I believe that the only explanation which seems probable is that treading the grape at harvest, could have taken place in the open, near the vineyards.14 The explanation for such an organization seems very logical, if one thinks about the needs that are triggered from wine-making.

At some point in time, and depending on the local wine-making tradition, the wine could have been decanted and filtered. Was this the case for Prehistoric wine? At least the evidence from Monastiraki seems to argue for the contrary. However, at Monastiraki, perhaps, chemical analysis needs to be done in many pithoi (jars) which do not preserve evidence of wine making and compare them to those that have evidence of dregs, in order to see whether there was a co-existence of different methods of wine preparation in the same settlement, or different grape products, at the same time.

7. Which were the types of cultivation?

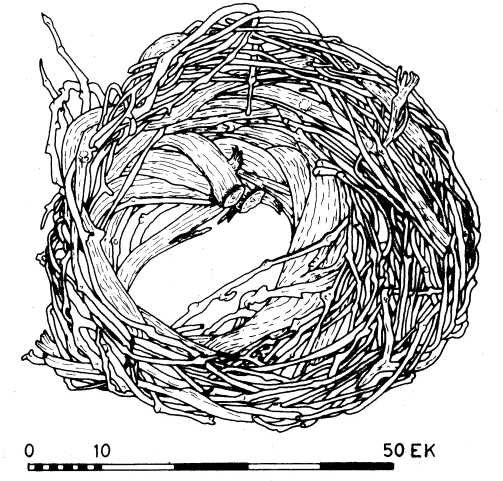

Grapevines can be cultivated in many ways, that is on trellises, on the ground, trimmed like a bush or climbing on trees. Special ways of pruning are still traditionally present in Greece, such as the example here from Santorini (Figure 6). On the fields, they can be mistaken for baskets, but it is just the way they are pruned.16 Why would such a multiplicity of cultivation and pruning not have existed also in the past?

There is evidence from Linear B (Palmer 1994, 57) that vines, in certain areas, could have been cultivated in between trees, especially fig trees, and the vines themselves could have been left to climb on these fruit trees, as they do in the wild state. For sure there must have been a variability of cultivation within and between areas. This is what we need to look for in the future.

8. Which were the levels of organization and what were the types of specialization of sites?

Cultivation of vines was, obviously, an integral part of agriculture but surely, the small farmer could not have had enough land to devote to vines alone, which, by definition, could only be grown in large enough fields, and only if they had excess land. Therefore, the more wealthy farmers had the possibility of vine cultivation to a level whereby wine could be produced in excess of personal needs. It is interesting to note that Minoan and Mycenaean palaces are kin systems as seen from the tablets and it looks as if they did not make their own wine (Palmer 1994, 187), but relied on producers in the countryside for their constant supplies. Monastiraki seems to have been such a centre, whereby landowners(?) produced wine for Phaestos and perhaps for other centres such as Agia Triada and Chamalevri17 in the north. Palmer (1994, 188) interestingly states that the wine tablets of the Mycenaean period (Linear B)18 were concerned with assessment of quality, collection and distribution but not with manufacture. The same cannot be claimed about the Minoan organization, without being able to negate it either. This leaves an open window to several scenarios, which might have operated at Monastiraki. It could have been a centre of wealthy people, i.e. fairly large landowners, who traded their produce to the Palace of Phaestos (south) and to the north coast, at such sites as Chamalevri. Another scenario might be that Monastiraki was inhabited by “traders” of wine, i.e. that their agricultural pursuits mainly concerned grape, grape products and little else, and they traded with other areas to supplement their dietary needs. A third avenue could have been that Monastiraki was inhabited by officials “kept” from Phaestos, whose remuneration was governed by the quality and production of their wine. The status of wine in the dialectics of power for those periods has been discussed thoroughly by Hamilakis (1996).

9. Epilogue

The early evidence of wine pressing is better documented from the north of Greece (Mangafa 1990; Valamoti 1998; Valamoti et al. 2007) than in the south (Knossos). At present, there is only a mere presence of the grape around the 5th millennium (grape pips and pollen) but, to date, no evidence has been uncovered from either archaeobotany or structures/artefacts of the vine-pressing process. Lack of evidence in this case cannot be accepted, though, as evidence of absence.

For the Middle Bronze Age, the site of Monastiraki is promising, in that it could provide evidence on elements of organization of vine agriculture, processing, production, consumption and even “trade”. Unfortunately, the Neolithic finds have not been able to provide inkling into the types of organization of wine production. The decipherment of Linear A, of course, will provide a new basis for the understanding of the archaeobotany, together with the similarities/ differences, within and between areas, of all the stages of wine production, from the type(s) of agriculture, ways of processing the grape, storage technology and control that producers enjoyed. What is very enlightening is that archaeobotanical finds, namely, seeds, can lead to a better understanding of the complexity of agricultural organization that existed, as early as the Middle Minoan Period, before the formation of the Neopalatial Period. In this case, archaeobotany can help put the texts, such as Linear B and Linear A – once deciphered – in context. However, at the moment, we have to sample systematically for archaeobotanical remains, and cooperate with scientists, in order to “decipher” more all the stages of vine cultivation, processing and wine production.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to a good friend, Marek Zvelebil who, at the zenith of his intellectual development, has left us. He always recognized and enjoyed good wine, so I decided it was an appropriate topic, close to his heart. For the invitation to present a paper, I would like to thank Jaromír Beneš and George Landers for English corrections. Thanks are also given to anonymous reviewers, whose comments helped to improve the text.

References

ASHTON, N. 2002: Ancient patitiria on the island of Megisti (Kastellorizo) and the reference in Dioscurides Pedanius, Material medica, to wine which was called Kretikos. In: Sweet-drinking Old Wine. The Cretan wine from the Prehistoric period to the modern era. International Conference at Peza, Pediados (1998), Heracleio, 147–160.

BOTTEMA, S. 1994: The Prehistoric Environment of Greece: a Review of the Palynological Record. In: Kardulias, P. N. (Ed.): Beyond the Site: Regional Studies in the Aegean Area. University Press of America, 45–68.

BOTTEMA, S., SARPAKI, A. 2003: Environmental change in Crete: a 9000-year record of Holocene vegetation history and the effect of the Santorini eruption, Holocene 13(5), 733–749.

BUXÓ, R. I CAPDEVILA 1997: Presence of Olea Europaea and Vitis vinifera in archaeological sites from the Iberian peninsula, Lagascalia 19 (1–2), 271–282.

HANSEN, J.M. 1991: The Palaeoethnobotany of Franchthi Cave. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

HAMILAKIS Y. 1996: Wine, oil and the dialectics of power in Bronze Age Crete: a review of the evidence, Oxford Journal of Archaeology 15, 1–32.

JACQUAT, C., MARTINOLI, D. 1999: Vitis vinifera L.: wild or cultivated? Study of the grape pips found at Petra, Jordan, 140 BC–AD 40, Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 8, 25–30.

JONES, G. 1984: Appendix 1: The LMII plant remains. In: Popham, M. R. (Ed.): The Minoan Unexplored Mansion at Knossos. BSA, supplement 17, 303–306.

KOPAKA, K., PLATON, L. 1993: Linoi Minoikoi. Installations minoennes de traitement des produits liquides, Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 117, 35–101.

KOPAKA, K. 1997: The vine and the wine in the Prehistoric Aegean. In: Conference Proceedings of the Hellenic Chemists, entitled Yesterday, today and tomorrow of the Cretan wine products. Herakleio, 21–44.

KOPAKA, K., CHRISTODOULAKOS, Y., MOSCHOVI, G., DROSINOU, P. 2001: Rock-cut presses in Gavdos. In: Proceedings of the 8th Cretological Conference in Herakleio. 1996, 557–80.

KROLL, H. 1991: Sûdosteuropa. In: Van Zeist, W., Wasylikova, K., Behre, E. (Eds.): Progress in Old World Palaeoethnobotany. Balkema, Rotterdam, 161–177.

LOGOTHETIS, V. 1962 : Les Vignes Sauvages (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. silvestris Gmel.) en tant que matériel primitif viticole en Grèce, Annuaire Scientifique de la Faculté Agronomique de l’Université de Thessaloniki 7, 139–182.

MANGAFA, M. 1990: The Plant Remains from the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age Site of Dikili Tash, Macedonia, Greece. MS. Dissertation. Deposited: University of Sheffield, Dept. of Prehistory and Archaeology.

MANGAFA, M. 2000a: The archaeobotanical study of the lake settlement of Dispilio in Kastoria, Eptakyklos 15, 189–199.

MANGAFA, Μ. 2000b: The use of plants from the Middle Palaeolithic until the Neolithic period – from foraging to cultivation. The archaeobotanical study of the Cave of Theopetra. The Cave of Theopetra – Twelve Years of Excavations and Research 1987–1998. In: Proceedings of an International Conference in Trikala. 6–7 November 1998, Athens, 135–137.

MANGAFA, Μ. 2002: The archaeobotanical study of the settlement. In: Chourmouziadis, G. (Ed.): Dispilio – 7500 years ago. University Studio Press, Thessaloniki, 115–134.

MANGAFA, M., KOTSAKIS, K. 1996: A new method for the identification of wild and cultivated charred grape seeds, Journal of Archaeological Science 23, 409–418.

MANGAFA, M., KOTSAKIS, K., STRATIS, I. 2001: The experimental charring of products of the grape vine and an investigation of its uses in antiquity. In: Bassiakos, Y., Aloupi, E., Fakorellis Y. (Eds.): Archaeometric Studies for Greek Prehistory and Antiquity. Greek Archaeometric Society, Athens, 495–505.

MANGAFA, Μ., KOUKOULI-CHRYSANTHAKI, CH., MALAMIDOU, D., VALAMOTI, T. 2002: Neolithic Wine: archaeological evidence from the Prehistoric settlement of Philippoi at Dikili Tash. In: Art and Craft in the grape-producing fields of Northern Greece. 9th Three-day Workshop, Adriani Drama, 25–27 June 1999, Athens, ΕΤΒΑ, 21–35.

NÚÑEZ, D. R., WALKER, M. J. 1989: A review of palaeobotanical findings of early Vitis in the Mediterranean and of the origins of cultivated grape-vines, with special reference to new pointers to Prehistoric exploitation in the Western Mediterranean, Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 61, 206–237.

OLMO, H. P. 1995: The origin and domestication of the Vinifera grape. In: McGovern, P., Fleming, S. J., Katz, S. (Eds.): The Origins and Ancient History of Wine. Gordon & Breach Publishers, 31–43.

PALMER, R. 1994: Wine in the Mycenaean Palace economy. Aegaeum 10. Université de Liège, Liège.

RENFREW, C. 1972: The Emergence of Civilization: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium B.C. Methuen, London.

RENFREW, J. 1979: The first farmers in southeast Europe. In: Kōrber-Grohne, U. (Ed.): Festschrift Maria Hopf. Rheinland Verlag GMBH, Köln, 243–265.

SARPAKI, A. 1992: Traditional methods of viticulture. In: History of Greek Wine. ETBA, 54–60.

SARPAKI, A. 1995: The archaeological presence and the visibility of the vine in Crete and in Greece in the Prehistoric period. In: Proceedings of the International Cretological congress, Vol: A (2). Rethymno, 841–861.

SARPAKI, A., BENDING J. 2004: Archaeobotanical assemblages. In: Soles, J., Davaras, C. (Eds.): Mochlos IC. Period III. Neopalatial Settlement on the Coast: The Artisans’ Quarter and the Farmhouse at Chalinoumouri: The Small Finds. INSTAP Academic Press, Philadalphia, 54–60.

SARPAKI, A., KANTA, A. 2011: Monastiraki, in the Amari region of Crete: some interim archaeobotanical insights into Middle Bronze Age subsistence. In: Proceedings of the 10th Cretological Conference (1–8 October 2006), Vol. A1. The Philological Society Chrysostomos, Chania, 247–270.

Shay, C. T., Shay, J. M. 1995: The flora and plant remains from Bronze Age deposits at Kommos. In: Shaw, J. W., Shaw, M. C. (Eds.): Kommos: an Excavation on the South Coast of Crete. Princeton University Press, 91–162.

SCHIEMANN, E. 1953: Vitis in Neolithicum der Mark Brandenburg, Züchter 23 (10–11), 318–327.

SHERRATT, A. 1987: Cups that cheered: the introduction of alcohol to Prehistoric Europe. In:Waldren, W., Kennard, R. (Eds): Bell Beakers of the Western Mediterranean: The Oxford International Conference 1986. BAR, International Series, Oxford, 81–106.

SMITH, H., JONES, G. 1990: Experiments on the effects of charring on cultivated grape seeds, Journal of Archaeological Science 17, 317–327.

STUMMER, A. 1911: Zur Urgeschichte der Rebe und des Weinbaues, Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 41, 283–296.

TERRAL, J.-F. 2002: Quantitative anatomical criteria for discriminating wild grapevine (Vitis vinifera ssp. sylvestris) from cultivated vine (Vitis vinifera ssp. vinifera). In: Thiébault, S. (Ed.): Charcoal Analysis: Methodological Approaches, Palaeoecological Results and Wood Uses. Proceeding of the 2nd International meeting of anthracology, Paris 2000. BAR, International series 1063, Oxford, 59–64.

TZEDAKIS, Y., MARTLEW, H. (Eds.) 1999: Minoans and Mycenaeans: Flavours of their Time. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

TZEDAKIS, Y., MARTLEW, H., JONES, M. (Eds.) 2008: Archaeology Meets Science: Biomolecular Investigations in Bronze Age Greece. Oxbow Books, Oxford.

VALAMOTI, S. M. 1998: Use of the vine in the area of Macedonia and Thrace during the Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age. In: Wine-making history in the area of Macedonia and Thrace. The fifth three-day workshop at Naousa. 17–19 September 1993, ΕΤBΑ, 137–149.

VALAMOTI, S. M. 2007: The archaeobotanical research of food in Prehistoric Greece). University Studio Press, Thessalonika.

VALAMOTI, S. M., MANGAFA, M., KOUKOULI-CHRYSANTHAKI CH., MALAMIDOU D. 2007: Grape pressings from northern Greece: the earliest wine in the Aegean? Antiquity 81 (2007), 54–61.

VICKERY, K. F. 1936: Food in Early Greece. Ares Publications, Chicago.

*Corresponding author. E-mail: a.sarpaki@gmail.com

1The vast literature on pottery studies related to drinks, and especially to wine, will not be discussed here. The importance attributed to wine in the formation of complex societies has been elegantly discussed by Renfrew

(1972) in his seminal book on the emergence of complex societies in the Aegean. This has been taken up by Sherratt (1987) and Hamilakis (1996) in other seminal studies about the importance of “drinks” including wine, which Sherratt looked at, in a wider chrono-geographic context.

2An important study of finds of Vitis in the Mediterranean and especially in the western Mediterranean was published by Nứñez and Walker (1989).

3The probability of the inhabitants harvesting wild grape is rather negligible for those time periods and those areas.

4The wild grapes used for the measurements by Mangafa and Kotsakis (1996, 410) were populations which were collected in the north of Greece, Western and Eastern Macedonia, whereas different populations of wild grapes in other parts of Greece and the Mediterranean also need to be measured. Moreover, other criteria need to be further identified and, most probably, ratios rather than strict measurements need to be identified and studied, e.g. the ratio of stalk length to total pip length (Smith, Jones 1990, 326; personal discussions with Glynis Jones).

5Mangafa, Kotsakis (1996, 410) only measured seeds from two vine varieties, Limnio and Asyrtiko and both obtained from Macedonia. There are many more grape varieties in Greece alone which need to be measured.

6Palmer 1994, 14, note 19 for the mention of earlier authors who claimed sedentism as a prerequisite to vine cultivation.

7Often referred as wineskins in the bibliography.

8A tripod cooking pot (EUM-30, Rethymnon archaeological Museum No. 3650) from Monastiraki is referred to as having contained resinated wine that was stored in an oak barrel (Tzedakis, Martlew 1999, 146). For the same pot (Beck et al. 2008, 33–34) refer to the find of oak lactone (Quercus). These are derived from the wood and transferred to the liquid. Therefore, according to the researchers, the presence of octanolide or nonanolide in Monastiraki sherd EUM-30 “can be explained by the use or storage in this vessel of wine ....that had earlier been processed or stored in an oaken container”. We do not have evidence of barrels before the time of Herodotus, so oaken wine presses could have been a possibility.

9Akrotiri is a typical site which has been totally covered by tephra (volcanic ash) in one moment in time and would have buried all structures complete with their contents. The absence of other wine-presses on the site makes the issue much more relevant.

10The exact time is changeable as it depends on the weather of a particular year, inasmuch as this has effects on the ripening stages of the grape.

11This agrees well with what Palmer (1994, 16) concludes from the study of Linear B.

12As indicated by the mention of wine and grapes in Linear B tablets.

13Even though a few more have been found since, the general picture does not change.

14Palmer (1994, 188) refers to KN Uc 160.4 where it is described that wine made from free-run must is sweeter and keeps better than wine made from pressed grapes, Also impressed sealings from the Wine magazine present further evidence that wine was produced from local landholders, where a minimum of 41 landholders were delivering wine. Therefore, at Knossos, we are aware that the wine was collected from several sources. Both at Pylos PY Er 880 pe-pu2-te-me-no land, lists vines and figs as its crop trees. Both also appear at Knossos KN Gv 863 where it seems that orchard growers trained vines to grow up support trees, so there it seems that vines were part of this tradition of orchard growing. Palmer’s (1994, 194) study of the Linear B tablets indicates that both palace centers at Pylos and Knossos and the houses outside the walls of Mycenae, relied on farmers throughout the kingdom to supply wine along with other agricultural products.

15Scenes of winemaking in the tomb of Khety (11th Dyn. 2050–2000 BC) from Egypt indicate that much of the processing was done in the open air.

16Although the soil in the summer is very hot and could burn the grape, the vines are left to trail on the soil, as the summer winds (the meltemia) are, generally, very strong and as a consequence, can damage the vine plants. In this manner, the plant is trimmed in such a way as to be protected from these and other winds, as the Cyclades are the windy islands, par excellence.

17Chamalevri, from the archaeobotanical studies (seed remains) indicates that it, probably, specialised in olive oil production.

18Linear A, as far as it has been deciphered – not adequately compared to Linear B, in order to make comparisons between them – mentions wine, but the interpretation of its organization is still obscure and can only be solved with its decipherment.

Figure 1. Distribution of wild grape (Vitis vinifera ssp. sylvestris), from Zohary and Hopf (2000, 154).

Figure 2. Akrotiri, Thera: wine press installation found in New Trench 58B.

Figure 3. Monastiraki, Crete: Storage rooms of Eastern Sector, based on finds of pithoi (storage jars).

MONASTIRAKI: Eastern Sector

Room 3 = 4 pithoi

Room 23 = 2 pithoi & figurines

Room 35a = 3 pithoi

Room 35 = 12 pithoi

Room 38 = 12 pithoi

Room 39a = 3 pithoi (at least)

Room 40 = at least 4 pithoi

Room 51 = 45 loomweights, grinding

tools & 1 pithos

Room 41a = 5 pithoi

Room 42 = 2 pithoi

Room 44 = 5 pithoi

Room 46 = 2 pithoi

Room 56 & 57 = 8 pithoi

Room 66 = 6 pithoi

Room 67 = 1 pithoi & sealings (K)??

Room 68 = 2 pithoi (K)??

Room 70 = 10 pithoi

Room 71 = lots of pithoi???

Room 81 = 1 pithos & sealings (K)??

Room 85 = 5 pithoi

Storage rooms = N17

Figure 4. Monastiraki, Crete: Plan of Eastern Sector with distribution of Vitis sp. finds.

Figure 5. Sealing, CMS II/I, No. 420 from Chrysolakkos Malia (Middle Minoan) of a man treading wine (?) in a vat.

Figure 6. Santorini (Thera), Greece: a traditional way of pruning the vines.

0 800 km

Table 1. Sites with Vitis sp. Finds in Greece.

|

List of Aegean sites with grape-pip finds (N=36) |

||||||

|

Sites |

E.N. |

M.N. |

L.N. |

E.B.A. |

M.B.A. |

L.B.A. |

|

Achilleion |

X(a) |

|||||

|

Sesklo |

X(a) |

X(b) |

X(b) |

|||

|

Argissa |

X(a) |

X(b) |

X(b) |

|||

|

Sitagroi I–II |

X(a) |

|||||

|

Dispilio |

X(a)(b)(c?) |

|||||

|

Arapi |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Dimini |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Iolkos |

X(b)(c) |

|||||

|

Orchomenos |

X(c) |

|||||

|

Toumba Balomenou |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Dikili Tash |

X(a)(21+) |

X(b)(>900) |

||||

|

Makri |

X(b)(20) |

|||||

|

Thermi B |

X(b)(1) |

|||||

|

Pefkakia |

X(b) |

X(b) |

||||

|

Agiasma Makrigialos |

X(b)(5) |

|||||

|

Mantalo |

X(b) |

X(b)(25) |

||||

|

Skala Sotiros-Thasos |

X(b)(11) |

|||||

|

Sitagroi III |

X(a) |

|||||

|

Kastanas |

X(b) |

X(b) |

||||

|

Assiros |

X(b) |

X(b)(c) |

||||

|

Dimitra |

X(b)(29) |

|||||

|

Theopetra Cave |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Franchthi VII |

X(a)(8) |

|||||

|

Lerna |

X(b) |

X(b)(1102) |

||||

|

Synoro |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Tiryns |

X(b) |

X(a)(b)(c) |

||||

|

Servia |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Orchomenos |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Athens |

X(b)(1) |

|||||

|

Agios Kosmas |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Nichoria |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Phylakopi |

X(c) |

|||||

|

Akrotiri-Thera |

? |

? |

X(b) |

X(a)(c) |

||

|

Mycenae |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Menelaion |

X(c) |

|||||

|

Drakaina Cave-Cephalonia |

X(b) |

|||||

Key: (a) = Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris Gmel.; (b) = Vitis sp.; (c) Vitis vinifera L. (italic) = water floated soil but not systematically; (bold) = systematically water floated; (italic + bold) = some areas collected randomly and some systematically; (normal lettering-not bold or italic) = collected randomly and mostly by eye; (number) = number of pips when known.

Table 2. Sites in Crete with finds of Vitis sp.

|

List of Cretan sites with grape-pip finds (N=14) |

||||||

|

Sites |

E.N. |

M.N. |

L.N. |

E.B.A. |

M.B.A. |

L.B.A. |

|

Chamalevri |

X(b)(c) |

|||||

|

Phaestos |

X(b) |

X(c) |

||||

|

Myrtos |

X(b)(68) |

|||||

|

Knossos |

X(b)–E.N.II |

X(b) |

X(b) |

|||

|

Knossos – unexplored mansion |

X(c) |

|||||

|

Chania-Kastelli |

X(b)(a) |

|||||

|

Malia |

X(b)(c) |

|||||

|

Monastiraki |

X(a)(c) |

|||||

|

Zakros – kato |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Thronos |

X(b)(c) |

|||||

|

Palaikastro |

X(b)(c) |

|||||

|

Mochlos |

X(b) |

|||||

|

Kommos |

X(c) |

|||||

|

Vathypetro |

X(b) |

|||||

Key: (a) = Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris Gmel.; (b) = Vitis sp.; (c) Vitis vinifera L. (italic) = water floated soil but not systematically; (bold) = systematically water floated; (italic + bold) = some areas collected randomly and some systematically; (normal lettering-not bold or italic) = collected randomly and mostly by eye; (number) = number of pips when known.

Table 3. List of sites with wine-pressing installations from Crete (after Kopaka, Platon 1993).

|

Treading/Pressing installations at Minoan sites on Crete (After Kopaka & Platon 1993) |

|||||||||||

|

Sites |

E.M.II |

M.M.I |

M.M.IIIA |

M.M.IIIB |

L.M.I |

L.M.IA |

L.M.IB |

L.M.II |

L.M.III |

L.M.IIIA |

L.M.IIIB |

|

Knossos |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||||||

|

Malia |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Gournia |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Myrtos |

4 |

||||||||||

|

Palaikastro |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|||||||

|

Zakros (kato) |

1 |

2 |

4 |

||||||||

|

Phaestos |

1? |

||||||||||

|

Prof. Elias-Tourtoulon |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||||||||

|

Kommos |

3 |

3 |

|||||||||

0 15 cm

0 15 cm

0 50 cm